Adam Potocki (1822-1872) was Artur’s and Zofia’s only surviving child. Brought up with his first cousins in Łańcut, having received an excellent international education and inheriting his parents’ significant estate undivided, he was viewed as a natural leader for Galician Poles subjected to Austrian rule.

Witnessing the short insurrection in Kraków in 1846 and as well the Paris riots in 1848, both quelled in blood, convinced Adam that armed revolts against established authority were counterproductive. Elected several times to represent Galicia in Vienna, Adam strove for greater political rights within the limits of the law. He also understood that improved representation and autonomy needed to be founded on an educated and economically independent middle class.

Adam Potocki, daguerréotype ca. 1855 by Alexis Gouin. © National Museum in Warsaw

He supported the enfranchisement of peasants, the modernization of agricultural methods as well as industrialization of a province which lagged significantly behind the rest of the Austrian empire. As a leading landowner in Galicia, he invested in local mining, rail and river transport, industry and banking ventures, with mixed success but the unwavering goal of promoting local development. He also financed Kraków’s first newspaper “Czas” (Time) which became the arbiter of political and cultural life in Galicia until 1918.

Adam naturally collaborated with the Czartoryski clan established at the Hôtel Lambert in Paris, even if the latter were generally supportive of armed action while the former favoured incremental progress. Deemed nonetheless dangerous by the Austrian administration, Adam was arrested on spurious charges, and eventually sentenced to 6 years in jail in 1850. Powerful family connections to the Vatican and, ironically, Tsar Alexander II of Russia, led to his being pardoned by Emperor Franz Jozef a year later. Adam, weakened by his incarceration, passed away prematurely at the age of 50.

His wife Katarzyna (1825-1907), born Branicka like his mother, shared her husband ideals of service to the nation, and devoted her life and considerable fortune to charitable causes. The Potockis were remembered in particular for the generosity of their support during the great fire of 1850 which ravaged a great part of Krakow.

Adam and Katarzyna finally realised oft-postponed plans of building a palace at their estate in Krzeszowice, just outside Kraków. Architectural plans commissioned by Adam’s grand-mother, Izabela Lubomirska, at the end of the 18th century never came to fruition, neither did his parents’ due to Artur’s premature death. Finally in 1850, the couple initiated works which lasted for over a decade. Set nearby water springs, in the vicinity of Krakow, it became the family’s summer residence and housed part of their important art collection. The estate was requisitioned by Nazi Gauleiter Hans Frank from 1939 until 1944 and later confiscated by the communist regime which turned it into a school and sanatorium.

Expand to Read More

Adam lost his father and his siblings at a young age. Not to be brought up alone, he spent his childhood with his cousins in Łańcut: Alfred, Artur, Julia and Klementyna. Adam and Alfred would grow very close, not unlike their respective fathers. They were taught in Polish, German and French. Zofia Potocka despatched her son Adam to complete his studies in Vienna, an obvious choice for an Austrian subject, but also and more unusually to Great Britain. After a month spent in Cambridge in 1839, he settled in Edinburgh for a year.

The time spent in the United Kingdom shaped Adam’s worldview. By visiting farms and factories, he observed first-hand the effects of the rapid modernisation of agriculture and industry through trade and technical progress. His social connections opened the door to the world of politics and the functioning of a parliamentary democracy built on a growing, city-dwelling, middle class. He befriended Lord Dudley Coutts Stuart, an enthusiastic supporter of the Polish cause, and Władysław Zamoyski who represented the Czartoryski clan in London. His cousin Alfred Potocki would follow in his footsteps by being appointed attaché to the Austrian Embassy in 1844.

The first test of Adam’s political leadership was the brief Kraków uprising of 1846. Following the treaty of Vienna of 1815, the city had enjoyed the privileges of an autonomous republic, administered by Poland’s three partitioning powers. Kraków’s youth now demanded greater autonomy, which had been curtailed following the failed uprising in 1830-31 in the neighbouring Grand Duchy of Warsaw, and set up a National Guard. While not disavowing the movement, Adam encouraged them to choose negotiation over violence. He argued Kraków’s case in Vienna, alas to no effect. The uprising was easily crushed, all the more that the Austrian authorities cynically exploited peasant resentment fuelled by poor harvests and lingering feudal obligations to their landlords, encouraging them to rebel against the local nobility. Armed peasants butchered several thousand landowners and burned hundreds of manors, while Kraków was incorporated into the Austrian empire, losing all its remaining rights. Divide et impera.

The whirlwind of revolution would soon engulf the whole of continental Europe in a chain reaction of nationalistic fervour. In February 1848, the social demands of the French worker class joined liberal political aspirations of the Parisian elites. The latter deposed king Louis-Philippe d’Orléans and founded the Second Republic. In March, the Viennese forced the resignation of Chancellor Metternich, hated symbol of conservatism. Hungarians and Italians demanded secession from the empire. Galician Poles formed a National Committee and a delegation led by Adam Potocki presented their demands in Vienna, which included self-rule and liquidation of serfdom, ignoring in the process similar demands of a large Ukrainian minority.

In April, the feudal agrarian system was duly abrogated in Galicia, a few months before the measure would be applied across the Empire. Ferdinand I announced the formation of a constituent Assembly, to be made of elected representatives of all the provinces, except for the Hungarians which were fighting a war of independence.

Adam travelled to Paris in June, hoping to enlist French support in favour of Galician autonomy. His natural interlocutor was Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, who had emigrated to Paris in 1833 and established Poland’s de facto political representation in exile, housed in the elegant Hôtel Lambert. Meanwhile, the French capital’s working suburbs rose up in arms against the young Second Republic. Caught unprepared, the new government called in the Army and the National Guard to restore order. Adam volunteered to join the latter and took part in the street battles. He said to have opposed arbitrary executions.

Elected in July 1848 to the new Assembly in Vienna, among nearly a hundred representatives from Galicia, Adam found it a frustrating experience. Like all members of the liberal aristocracy, he was guided by a natural tendency towards compromise and incremental change, motivated by his social and economic conservatism and first-hand experiences of revolution and bloodshed. He found it difficult to reconcile the more extreme economic demands of the agrarian masses, the nationalistic intransigence of the intellectual elite and émigré circles, and the increasing reluctance of Franz Jozef I, who replaced his feeble-minded uncle in December 1848. In fact he gave up his parliamentary seat before the end of the year.

Still in control of the army, the imperial administration bombarded into submission recalcitrant cities and provinces, starting with Vienna in September 1848. Kraków and Lwów would fall in line before the end of the year. The quasi secession of Hungary, which had been accepted in April 1848, was invalidated by military intervention. In March 1849, the reformist Constitution drafted by Parliament was replaced by an absolutist one, restoring the central authority of the Emperor.

Adam’s involvement in political affairs both at home and abroad generated suspicion in Vienna, yet his social position should have insulated him from any repression. All of Galicia was thus dismayed when he was arrested in September 1851, interned in Kraków and later transferred to Vienna. A year later, already in poor health, he was sentenced to six years in jail on fabricated charges of “subversive activities aiming at the restoration of an independent Polish state”. Ironically all appeals for clemency at the Court by his wife and mother were fruitless. More effective were the interventions of his sister-in-law Elżbieta Vorontsova (née Branicka), whose husband Michael, viceroy of the Caucasus, was a powerful figure. Diplomatic pressure was successfully applied through the Russian embassy in Vienna, and Adam was pardoned by the Emperor Franz Jozef in October 1852. For the next decade he would concentrate mostly on private affairs.

The events instilled in Adam Potocki a profound dislike for armed rebellion as well as a comforted him in the idea that social injustice and economic backwardness were the first barrier to greater political rights. He would concentrate his energies and capital in supporting economic progress through the establishment of agrarian societies, investing in railroad ventures and industry (for ex. the Zieleniewski heavy machinery works, which exists to this day). In 1848 he financed the creation of “Czas”, the first daily newspaper to be published in Galicia, and saved it from bankruptcy in 1870. “Czas” provided the Galician establishment with a powerful political medium and served as a breeding ground for a new generation of literary and political talent, lasting until 1918.

In reality the Habsburgs’ conservative turn would only last until the next crisis, as the empire was caught between the crossfire of rising German, Italian, Hungarian and Slavic nationalism. Weakened and nearly bankrupted by military defeats against the French and the Piedmontese in 1859 and Germany in 1866, Franz Jozef was forced into gradual compromises, devolving self-rule to his empire’s constituent nations in order to maintain its unity. Austria ceded Sardinia and Piedmont to the kingdom of Savoy, leading to the creation of Italy in 1861. The latter would also absorb Venice and its province as a payback for joining Prussia in its war against Austria in 1866.

In parallel, the Emperor granted a new Constitution in February 1861 which established a bicameral parliament, with an upper chamber whose members were appointed for life by the monarch and an lower chamber, composed of representatives elected by the regional assemblies. Political and national representation was restored but still rested on the Emperor’s ultimate assent and on compromise between diverse national factions dominated by a German speaking majority. The Hungarians rejected this arrangement all together by refusing to participate in the Lower House.

Adam returned to politics as a member of the lower chamber in 1861. He sought to consolidate political loyalties between the land-owning nobility and the peasantry around a gradual path towards self-rule, starting with the use of Polish in national administration and education, wanting to avoid the faults of 1848 when Vienna easily defeated Polish demands by playing on economic divisions. His cousin Alfred followed the same path, but would eventually be appointed to the upper chamber as well.

At precisely the same time a second uprising was brewing in Russian-occupied Poland. Student manifestations were violently suppressed in Warsaw, starting a cycle of violence which would culminate in a poorly organised armed insurrection in January 1863 and its inevitable repression. Adam disapproved, but maintained party discipline in Vienna and sought French support, obtaining an audience with Napoleon III in Paris which yielded nothing. He hosted Charles de Montalembert at his Krzeszowice estate that summer. An ardent supporter of the Polish cause, the latter would publish a pamphlet titled “A Nation in Mourning: Poland in 1861”. In 1863, Adam and Katarzyna opened a field hospital for wounded refugees from the failed final clashes in Volhynia.

The resounding Austrian defeat against Prussia at Sadowa in June 1866 accelerated internal political change. Vienna had to cede the leadership over the German states to Prussia and was forced into a compromise in 1867 with the Hungarian elites, creating a dual kingdom of Austria and Hungary, where only military and foreign affairs were run as a common domain.

While the Hungarian compromise was being negotiated, Galician Poles pressed their advantage. Adam Potocki, heading the conservative fraction of the Polish circle at the Chamber in Vienna, submitted a memorandum to the Emperor proposing self-rule in exchange for loyalty to the monarch. Such a compromise faced opposition on both sides and would not pass muster. Nonetheless Vienna acceded to long-time demands on the use of Polish as an official language, autonomy in local administration and education. Adam Potocki would be actively engaged in the former, while his cousin Alfred, more trustworthy in the eyes of Vienna was appointed to ministerial posts. Eventually, as Russia became the main threat to Austrian interests in the Balkans, Polish elites would be increasingly co-opted into the army and the diplomatic corps.

Adam Potocki was not a natural politician and never built a stable political following. He led out of a sense of duty, preferring to spend his time on private or local affairs. With his wife Katarzyna, the couple devoted much of their fortune to charitable or educational causes. The great fire of 1850 which devastated a third of the city of Kraków revealed their generosity.

Adam died in 1872 and was buried in the family crypt in Krzeszowice. Aged 50, he passed away prematurely, just as Galicia was entering a period of remarkable economic and cultural development. The couple had seven children, of whom Artur, who also died prematurely; Andrzej, appointed governor of Galicia, was murdered in Lwów by a Ukrainian nationalist in 1908, Róża Raczynska; Zofia Zamoyska.

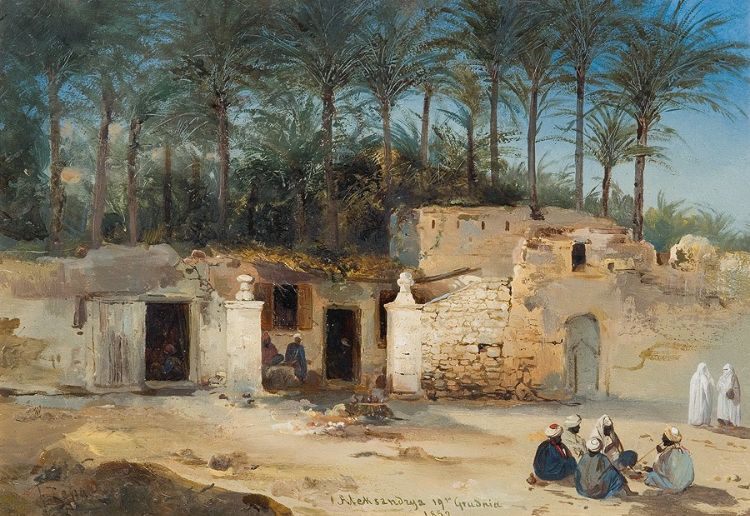

Upon his release from prison in October 1852, Adam and Katarzyna set out for an eight-month long trip to Egypt, Lebanon and Palestine. Since Muhammad Ali Pasha, the founder of modern Egypt, had lifted restrictions on travel by non-Muslims, a few privileged Europeans took a growing interest in ancient Egypt and the Near East.

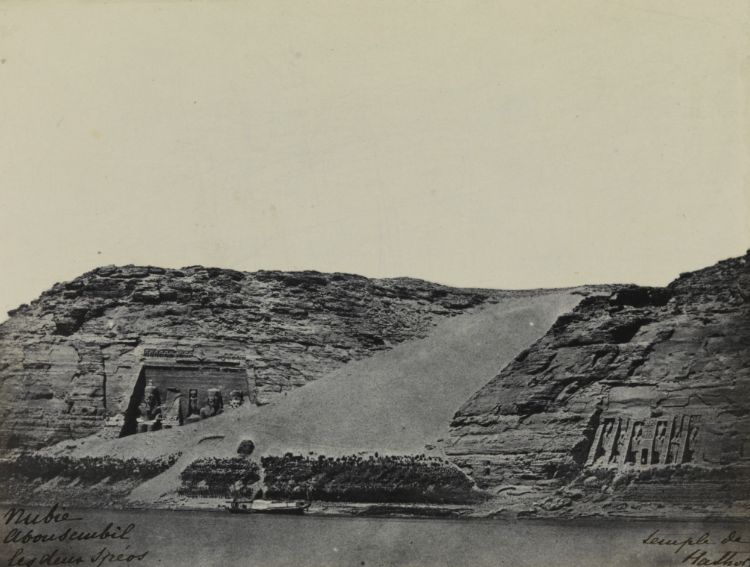

The Potockis sailed down the Nile all the way to Abu Simbel, visited the Roman ruins of the Beqaa Valley and prayed at the Holy Sites in Palestine. Adam must have been inspired by his grand-father Jan Potocki, who had explored the Muslim world from the Caucasus to Morocco in the late 18th c [link]. The couple was accompanied by journalist Maurycy Mann of the “Czas” newspaper and artist Franciszek Tepa to document the expedition.

The Potockis also acquired several rare photographs from local Europeans who had set-up shop in Beirut and Cairo, among whom Maxime du Camp. These rare and fine illustrations await rediscovery and can be viewed online.

The couple were in fact active and early collectors of photographs, acquired mostly from Parisian studios, among whom Alexis Gouin and Gustave Le Gray. The Potocki collections were nationalized in 1946 and are now part of the Warsaw National Museum.

© 2023 Potocki Wódka. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

You must be of legal age in your country to view the contents of this website.