Nicolas Potocki – Paris – XIX

Nicolas Potocki (1845-1921) was the grand-son of Felix Potocki, Poland’s and perhaps Europe’s greatest private landowner. Felix is alas mostly remembered for having sided with Catherine the Great by forming the Targowica confederation in 1791, against the last Polish king and the authors of May 3rd Constitution, among whom some of his relatives. Nicolas’ father, Mieczysław, was born to Felix’s third wife, a beautiful and notorious Greek courtisane.

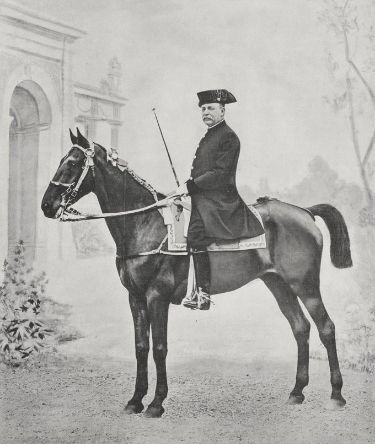

Nicolas Potocki by François Flameng, 1917. © CCI Paris Ile-de-France

Born in St-Petersburg and raised in Paris, Nicolas inherited both great wealth and his grand-father’s sad legacy of having placed private interest over the common good. He married Emanuela Pignatelli in 1870.

The couple shared much in common, but would soon grow estranged. Both had grown-up in Russia, had a chaotic family life and were descended from families whose histories were tied to states, Naples and Poland, which had disappeared from the map. Manuela squandered her husband’s wealth while entertaining the Parisian intellectual and social elite of her time. She lives on as a fictional character in many novels of her era, inspiring in particular her close friend Guy de Maupassant.

Childless, the couple left behind a Parisian landmark at 27 avenue de Friedland which is known as the Hôtel Potocki. Its imposing façade, impressive marble staircase, heavy bronze door cast by Christofle are a fine testament to the period of economic boom and wholesale redevelopment which gave Paris its current architecture.

The palace was sold by Nicolas’ heir, Alfred Potocki, to the French Government in 1923. The stables were replaced by reception areas, designed by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, a famous signature of the Art Deco movement. It since houses the Chamber of Commerce of city of Paris.

Expand to Read More

Nicolas’ father, Mieczyslaw Potocki, born in 1799, was the second son of Felix Potocki and Sophia Glavani, primo voto Witt. He hardly knew his father who died in 1805. Brought up without much supervision, he ended up turning against his mother who tried to disinherit him in favour of his elder brother Alexander. Clever, impulsive, Mieczysław spent most of his early life defending his fortune, often by dubious methods.

His love life resembled his business dealings. His first marriage to Delphina Komar was childless and brief. Beautiful and talented, Delphina Potocka moved to Paris where she impressed and inspired many artists, such as the poet Zygmunt Krasinski and Fryderyk Chopin.

Mieczysław first and favoured son, Grégoire, was born out of wedlock to a local maid. The second was Nicolas. His mother, Emilia Świejkowska, Mieczysław’s second wife, soon divorced him, sued him for ill-treatment and moved to St-Petersburg with young Nicolas.

Mieczyslaw left Russia under a cloud but with the considerable proceeds from the sale of the Tulczyn estate to his niece, Maria Strogonoff, in the late 1860s. He settled in Paris, invested in real estate and the stock market, and summoned his two sons to join him. Their next-door neighbours on Avenue Montaigne were two charming Italian sisters, Emanuela and Gaetana Pignatelli, who had spent their childhood in St-Petersburg.

The Pignatellis were a distinguished Neapolitan family, which boasted Pope Innocent XII among their more illustrious members. Their mother Rosa, prematurely widowed, married an older uncle of her first husband, Gennaro Capece Galeota, the last ambassador of the Kingdom of Naples in Russia.

After the reunification of Italy in 1861, the couple split and Rosa and her daughters settled in Rome. But her numerous high-profile affairs led the Pope to expel her. She eventually moved to Paris with her girls.

Those youthful and carefree encounters were marred by the war of 1870-71, opposing France and the Northern German Confederation. By January 1871 the Germans had surrounded the French capital and were bombarding it daily. Grégoire, dashing and brave, joined the national guard. Nicolas and Manuela, freshly engaged, seized an opportunity to escape the siege by hot-air balloon under the cover of darkness and made their way to Belgium. They joined Mieczysław in London where they married a year later.

The young couple returned in 1871 to a city scarred by war and revolution. Grégoire had meanwhile died in tragic circumstances, probably trying to defuse unexploded ordnance. Mieczysław, heart-broken, did not like Manuela much and was disappointed by the absence of grand-children, constantly threatening to disinherit his son. The trio, living under the same roof at Avenue de Friedland, quarrelled endlessly. Thankfully, the irascible and increasingly paranoid Mieczysław changed his mind on his deathbed in 1878.

Nicolas inherited a large townhouse located at 27 Avenue de Friedland with a spacious back garden. Seeking to increase its size, he acquired in quick succession three adjoining buildings on rue Chateaubriand (no 14, 14bis, 16) and one on rue Balzac (no 14), thus ending up owning almost the whole block. The couple hired architect Jules Reboul to rebuild and expand the façade on Avenue de Friedland and remodel the palace interiors. An imposing bronze door led to a wide staircase clad with precious marbles and onyx, reminiscent of the steps of the contemporaneous Garnier Opera house. The door and electric-arc lamps were designed by Christofle. Alfred Potocki would later have the latter installed in Łańcut where they illuminate several facades to this day.

The plot located at 16 rue Chateaubriand was transformed into spacious and luxurious stables, with stalls for three dozen horses, a rose marble fountain and a two-storey garage for several carriages, accessible by electric elevator. It formed the setting for an inaugural party Nicolas and Manuela gave in May 1882, as the palace was still being finished.

The couple happily took part in races and horse shows which punctuated the spring/summer social season, but soon grew apart. Manuela spendthrift habits annoyed Nicolas, who took no interest in his wife’s intellectual interests and increasingly ignored her. She found refuge in a hyperactive social life and in a circle of admirers, whom she hosted Avenue de Friedland. They were mostly older men attracted by her easy-going hospitality, fascinated by a combination of childlike beauty, cynicism beyond her age and a predilection for contradiction sharpened by a quick repartee.

The grand surroundings of the Hôtel Potocki became the venue of weekly reunions of the “Club des Macchabés” or “Stiffbody Club”. Manuela, known as “The Boss” (“La Patronne”) to insiders, distributed gratifications and humiliations to a faithful group of intellectuals, artists and dandies.

The men meekly accepted her despotism in exchange for refined meals, brilliantly entertaining, if not outright decadent, conversation. Most of the club members are today forgotten, except for Guy de Maupassant, who became a close friend. One could venture the comparison between Manuela and Boni de Castellane, without the talent for reinvention he displayed after his wife, the wealthy American heiress Anna Gould, grew tired of his extravagant lifestyle and kicked him out.

Nicolas divorced Manuela in 1887 but gave her a generous allowance. She moved into a spacious apartment a few blocks from her former home, where she continued to entertain “le tout Paris”. She still could not run a balanced budget and, hounded by her creditors, sued Nicolas twenty years later for half his fortune. The attorney representing her was Raymond Poincaré, future Prime Minister and President of the Republic. Nicolas won the case but agreed to nearly double Manuela’s allowance.

Nicolas found peace with a simpler woman, Mathilde Avignon. She was much younger, attractive and self-effacing. They spent much time at La Grange-Colombe, away from the city humdrum, tending to their garden of exotic species. Nicolas continued to organise shoots and four-in-hand coach driving competitions (aka “drag driving”), which were fashionable in the last decade of the 19th century. He had always been generous with needy compatriots and worthy Polish causes, inspiring Manuela to nickname his townhouse “le Crédit Polonais”. Among his numerous guests was a young pianist from Łódż, Artur Rubinstein, whom he grew very fond of and who reciprocated his friendship.

World War I brought an end to the gilded age. Manuela’s beauty, fortune and friends gradually abandoned her. Witnesses to the passing of time such as Marcel Proust and Robert de Montesquiou, who had once sung her praises, now announced her social demise. She died in 1931, lonely and forgotten.

Perhaps wanting to compensate for his lack of courage in the previous conflict, Nicolas supported the war effort with dedication. He funded a hospital with 80 beds for wounded soldiers at his country estate in Le Perray. Once the Polish Army was formed in France in the summer of 1918, the facility was repurposed to look after Polish volunteers. Nicolas was one of the few civilians invited to the official ceremony during which the 1st Polish Division received its regimental flags. It was held close to the front in Champagne, where the Poles were already fighting. He even considered bequeathing his hôtel particulier to the resurrected Polish state to serve as its embassy in Paris, but the plan never came to fruition.

Nicolas died in June 1921, choosing his nephew Alfred Potocki as his sole heir. His passing had been preceded and succeeded by a fierce battle between other potential claimants, who tried to question Nicolas’ mental health. Marshal Pétain, General Weygand and Prince Albert I of Monaco were asked to testify to the contrary. Alfred hired a well-connected notary to handle the inheritance.

The Hôtel Potocki was sold to the French Government in 1923. The adjoining chapel and garden of the Holy Sacrament congregation which Nicolas had purchased and leased back in 1902, were sold to the religious order. Mathilde Avignon received the usufruct of the country house in Le Perray, his smaller Parisian home at no 5 avenue du Bois as well as a generous pension. None of Nicolas’ closer friends – like his fencing master – and relatives were forgotten, nor was every member of his staff.

He donated three paintings to the Louvre Museum, of which a Rembrandt, which had belonged to last king of Poland, but whose attribution was later downgraded. The municipality of Rambouillet received an endowment for charitable purposes, so did the village of Montrésor which was tasked with the maintenance of Nicolas’ grave and those of his parents. Finally, his beloved Société de l’Étrier was to receive 200,000 francs to fund a prize in his name.

Nicolas’ inheritance, worth approximately 40 million francs, revived Alfred’s fortune. His finances had been severely affected by the destructions brought about by three years of Austro-Russian offensives and counter-offensives in Galicia as well as the loss of his land holdings in the Ukraine following the Bolshevik revolution. Even if two thirds of the estate went to settle taxes and other obligations, the balance still amounted to a significant sum.

The intoxicating atmosphere of the roaring twenties adding to the exuberance of youth, Alfred bought polo ponies and Rolls Royce motorcars in England, invited his brothers and cousins to a shooting safari up the Nile. He gave a final party Avenue de Friedland for 700 people and acquired a smaller townhouse in Neuilly, just outside Paris, retaining some of Nicolas’ house staff. Yet the majority of Nicolas’ inheritance was invested in Poland, newly independent but exhausted and impoverished after six years of conflict.

Alfred brought all the family objects, most of which originated from Felix’s palace in Tulczyn, to his castle in Łańcut. At the behest of the Polish government, he acquired a stake in the vast German coal and steel complex – Königs und Laura Hutte – in Upper Silesia. This rich industrial region had been attributed to Poland in 1923 with the critical support of France, following four years of civil war. Warsaw was anxious that this strategic industrial base should be controlled by domestic capital. Alfred Potocki obliged.

Nicolas’ fortune, rooted in his family’s vast land holdings in the Ukraine, accumulated in the 17th century, partitioned in the 18th century and shrewdly reinvested in French real estate, banking and industry in the 19th century, was consumed within a generation in the 20th century. Stifling French taxes and Poland’s geopolitical predicament were to blame. A magnificent Parisian landmark remains however, as testament to an ancient friendship uniting the two nations.

Nicolas was a practical man with a passion for “sport”: riding, fencing, shooting, fishing, and built his life around it. His townhouse in Paris included luxurious and modern stables as well as a fencing hall. He also acquired a shooting estate in Le Perray, near Rambouillet, neighbouring that of the French presidents. His hunting parties were run to a high standard and Presidents Loubet and Faure regularly asked him to entertain visiting officials, such as the King of Spain or Russian Grand Dukes.

Riding however was his true passion and pride, whether on a saddle or driving a four-in-hand. Nicolas was an active promoter of the sport and a member of several coach driving societies. In 1909 he became president of the Société de l’Étrier he had founded with a few riding enthusiasts in the Bois de Boulogne, and which exists to this day.

Artur Rubinstein recalls in his memoirs how Nicolas, who generously supported him as a promising pianist, tried to give him riding lessons, to little avail. He had more luck with Alfred Potocki, his relative, whom he introduced to the sport and eventually bequeathed most of his fortune to.

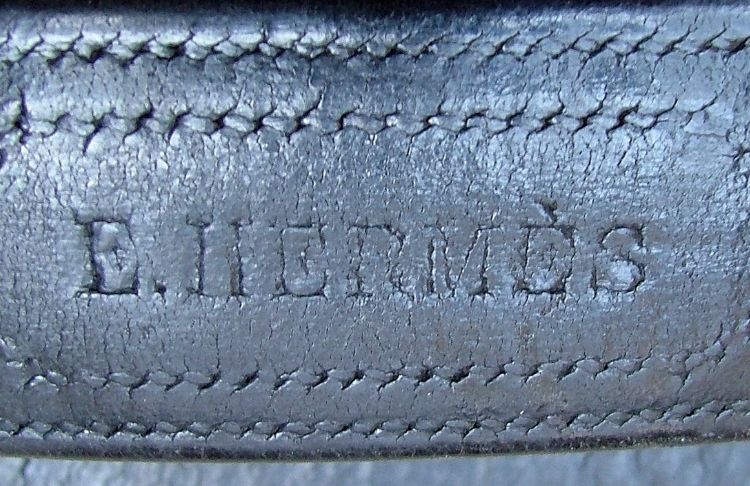

Alfred brought back to Łańcut only a few carriages, including complete harnesses and liveries for the footmen and postilions. They today form part of the Łańcut Museum collection, which includes rare pieces commissioned by Nicolas with saddle-makers Hermès and Duprey.

Alfred in fact used a Parisian calèche à la d’Aumont to drive the visiting Duke and Duchess of Kent in 1937 from the station to the castle.

© 2023 Potocki Wódka. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

You must be of legal age in your country to view the contents of this website.