Stanisław “Revera” Potocki – Stanisławów – XVII

Stanisław „Revera” Potocki (1589 -1667) was a figure immortalised by Henryk Sienkiewicz in his famous 19th century historical trilogy “With fire and sword”. As Grand Crown Hetman Stanisław defended Poland’s vast dominions against multiple and powerful enemies threatening its very existence.

The Polish Commonwealth, ruled by the elected kings of the Swedish Vasa dynasty, was perennially threatened in the South by the expanding Ottomans and their occasional Tatar allies, by the Muscovites in the East and the Swedes in the North. Poland’s King Wladysław IV had originally planned to wage war on the Ottomans with the help of the Cossacks, hoping to gain definitive control of the Black Sea coast. Things took a turn for the worse when Bogdan Khmelnitski gathered the Cossacks into a huge army and allied with the Crimean Tatars, effectively turning the tables on the Polish king. In a series of epic battles fought between 1648 and 1652, Cossacks and Tatars chased the Poles out of right-bank Ukraine.

A weakened Poland whetted the appetite of Alexei Romanov of Muscovy and Karl X Gustav of Sweden, who hoped to snatch the Polish crown from his cousin Jan Kazimierz. The former sealed an alliance with the Cossacks in 1654 and occupied Lithuania, while the latter swept through central Poland in 1655 practically unhindered, in a plundering frenzy reminiscent of the Viking raids of yore.

Stanisław Potocki was given overall command of the Army in 1654 and tasked to rebuild it as an effective fighting force at the most critical of times. He fulfilled his mission and capped his career with a great victory in Cudnów (1660) where he routed Poland’s eastern foes.

Having spent a lifetime at war, he had little time to administer his estates. Nonetheless, Stanisław helped his son eldest son Andrzej found a fortified city in the foothills of the Carpathians in 1662, at the end of the Cossack wars. Andrzej, also an important figure in Polish military history, would develop it and name it in his father’s honour: Stanisławów. The city flourished as a fortress and a multicultural trading hub until the partitions a century later. It was renamed Ivano-Frankivsk by the Soviet authorities in 1962 after a Ukrainian author and political activist.

Expand to Read More

Born into a family of military leaders, Stanisław Potocki was thrust into war from an early age. After studies in Basel under Calvinist tutors, he travelled to France and the Netherlands to complete his education. He returned to Poland to take part in campaigns against Muscovy, the Ottoman Porte and Sweden under the leadership of Great Crown Hetman Koniecpolski, gaining in consequence prestigious and lucrative appointments as governor of Poland’s eastern voivodships.

Stanisław led cavalry regiments, either Crown troops – the so-called “Winged Hussars” – or Cossacks recruited in the borderlands. Koniecpolski’s untimely death in 1646 preceded the election in 1648 of a new king, Jan Kazimierz Vasa, and the emergence of a grave threat to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s very existence, the Cossack rebellion led by the charismatic Bogdan Khmielnitski.

Stanisław joined the king’s war council and waged a difficult campaign with insufficient resources. Unable to pay their recruits, the Poles were faced with repeated rebellions and desertions among their ranks. Potocki was forced to pledge his own assets to settle wage arrears. He was named Field Hetman in 1652 and voivode of Kiev in 1653, a critical responsibility in defending Poland’s largest and easternmost province.

Upon learning that the Cossacks had signed an alliance with the Muscovites in Pereiaslav in January 1654, the king decided to march against them, finally granting Stanisław overall command of the army. With the help of Tatar reinforcements, he won an important battle at Okhmatov in the thick of the winter of 1655 but failed to encircle and completely defeat the forces of Khmielnitski and Sheremetiev. His army subsequently conducted punitive campaigns “by fire and sword” against the local population supporting the Cossack rebellion.

Meanwhile Sweden’s new king, Karl Gustav Wittelsbach, chose to pounce. Taking advantage of Poland’s entanglement in the East, the Swedes invaded central Poland in the summer of 1655 and ransacked it, practically unhindered, taking Kraków in October. This period, lasting until 1660, is remembered in Poland as the “Swedish Deluge”. At about the same time Moscow had attacked Lithuania, occupied Wilno, massacred its population and thoroughly plundered the city. Powerful Lithuanian magnates effectively broke the union with Poland by seeking the protection of Sweden, while many of the central provinces occupied by the Swedes switched allegiance all the more easily that Jan Kazimierz was deeply unpopular. The integrity of Poland seemed in jeopardy and its king sought refuge in neighbouring Habsburg Silesia.

Short of funds to pay his troops, abandoned by most of his lieutenants, Stanisław Potocki reluctantly gave in and swore allegiance to Karl Gustav in November. Meanwhile, the successful resistance of the monks of Częstochowa, whose rich monastery the Swedes had laid siege to, revived Polish hopes and united the population, the nobility and its military leaders against the invaders. Hetman Potocki and his troops joined the confederation at Tyszowce in December 1655. The king returned to Poland the following month and agreed, during a historic council held at Łańcut castle, to support the war of liberation.

The Polish King needed allies and enlisted the support of the Crimean Tatars. Khan Mehmed IV Girey assented all the more readily that he had been recently betrayed by Khmielnitski in favour of Moscow. In turn, Karl Gustav, who had been forced onto the defensive, signed an alliance with the Hohenzollern ruler of Prussia, a vassal of Poland since 1525. He also split the army’s command between the younger Stefan Czarnecki and Hetman Potocki.

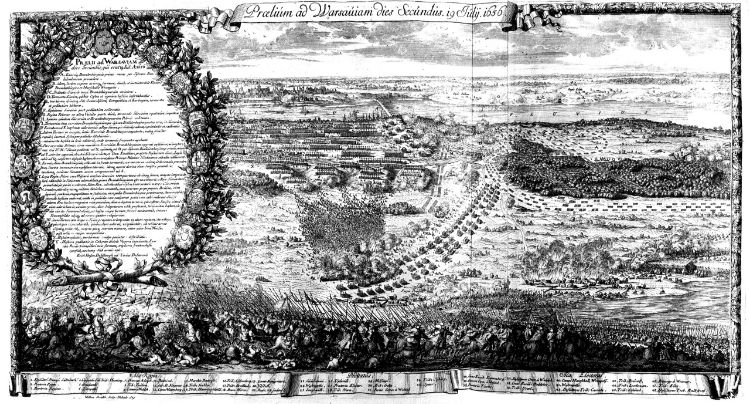

The Poles, led by Czarnecki and supported by Tatar cavalry, engaged the Swedes outside Warsaw in the summer of 1656. It was a battle of gigantic proportions for the time, involving a total of 70,000 men. The Poles, though defeated, managed to retreat but left Warsaw undefended. The city was thoroughly looted: many Polish treasures can today be found in Stockholm libraries, museums and palaces. The population of the right bank Praga district was massacred.

Stanisław Potocki directed his troops towards Kraków, where George II Rakoczy, prince of Transylvania, having opportunistically allied to Karl Gustav, occupied the city in the wake of the Swedish retreat. The Poles finally ousted him in 1657.

Things begin to change in the East after the death of Khmielnitski the same year. His successor Ivan Wyhowski sought an arrangement with Poles which led to the signature of the Union of Hadiach in September 1658, ratified by the Sejm and King Jan Kazimierz the following year. It foresaw the creation of a trinational state with the addition of a Grand Duchy of Ruthenia (see map) to the existing union of Poland and Lithuania.

Giving the Ukrainian Cossacks political rights equal to those enjoyed by the Polish and Lithuanian nobility, and guaranteeing their right to practice the Orthodox faith, it was meant to replace the Pereiaslav alliance signed four years earlier with Muscovy and solidify Poland’s hold on its eastern provinces. It was not to last alas, as Moscow managed to oust Wyhowski and convince Bogdan Khmielnitski’s son, George, to renege on the agreement. It was a fateful decision for the Ukrainians who would soon find themselves under full Russian domination.

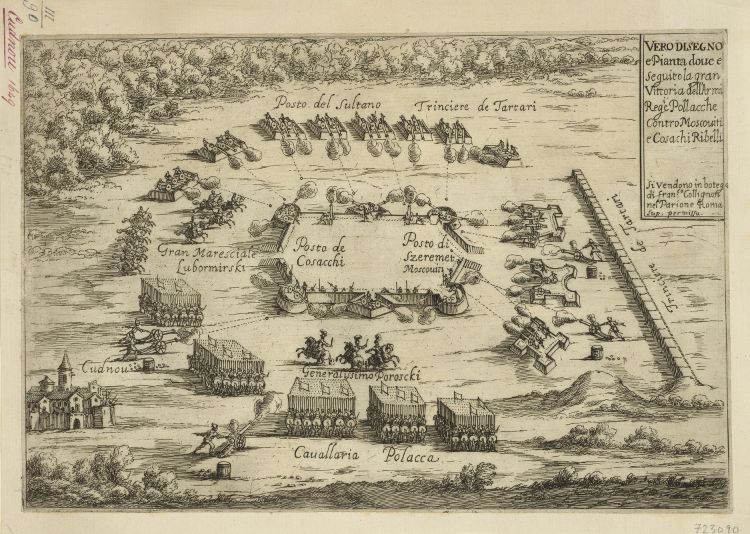

Having finally ousted the Swedes at the peace of Oliwa in May 1660, the Poles could turn the full strength of their army to the East. Under Hetman Potocki, thirty thousand troops complemented by twelve thousand Tatars under Murat Girey, dealt a decisive blow to the Ukrainian-Muscovite alliance at the battle of Cudnów in October 1660. Completely defeated, Sheremetiev was forced to capitulate and eventually taken prisoner by the Tatars. As so often in their history, the Poles did not properly exploit this decisive victory, failing to expel the Russians from Kiev. But for Potocki it capped a long and tumultuous career.

His two sons, Felix and Andrzej, who fought with their father would continue to serve under Kings Wiśniowiecki and Sobieski, opposing the rising power of the Ottomans, earning respectively the titles of Grand Crown Hetman and Field Crown Hetman.

In hindsight, Poland had achieved peace at great cost as it allowed its hereditary enemies to gain strategic advantage. Fredrick Wilhelm Hohenzollern, having fought the Poles with Carl Gustav outside Warsaw 1656, switched allegiance four years later in exchange for Prussia’s emancipation from Polish overlordship. The move paved the way for Prussia’s emergence as a European power with fateful consequences. Likewise, although defeated on the battlefield, Muscovy had wrested Kiev from Polish control, thus laying the spiritual cornerstone of the Russian empire proclaimed by Alexei’s son, Peter the Great, in 1721.

Andrzej Potocki decided to erect a fortress on land he had acquired in 1658, situated where the two Bystrytsa rivers converge. The new stronghold was intended to supplement the old fortress of Halicz in defending the approaches of Polish of Red Ruthenia. This area, known as Pokucie in Polish, set between the Dniestr river to the East and the Carpathians to the West, was a natural corridor used by the Commonwealth’s immediate neighbours, Transylvanians and Vallachians (today’s Moldova), or more ominously by the Ottomans. Fortified strongholds were thus essential in keeping them at bay.

Andrzej commissioned the Crown’s chief military engineer, a Piedmontese named Francesco Corazzini, to build a modern defensive system with a hexagon shape. It was completed in 1662 and named Stanisławów after Andrzej’s father and eldest son. A French architect, Charles Benoit was later commissioned to build a town hall, a church and a family seat.

Stanisławów benefited from the outset from Magdeburg laws allowing it to trade freely, attracting many Armenian and Jewish merchants. The city quickly became an important defensive outpost on the south-eastern edge of Poland, a vibrant economic multi-ethnic center as well as a place of learning. Following the example of Zamość founded a century earlier, Andrzej set up an academy staffed by professors from the Jagellonian University in Kraków. His son Józef invited the Jesuit order in 1714 to found a college which functioned for nearly a century.

The Potockis’ ownership of Stanisławów ended with the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. Isolated from the new centres of power and trade, the city gradually turned into a sleepy outpost of Austrian ruled Galicia. The old fortifications were torn down and the city expanded, yet retained its ethnic and religious diversity, enriched by an influx of German-speaking settlers.

World War I brought massive destruction as Stanisławów changed hands several times between the Austrians and the Russians. From 1917, Bolshevik marauders and Ukrainian nationalists took control. Volunteers managed to fend off the former, while the Polish Army equipped by the French finally took control of Stanisławów in May 1919, which led to its subsequent incorporation into independent Poland.

On September 17th 1939, the city was occupied by the Red Army and in its wake the NKVD which executed or deported the city’s elites. In July 1941, the Nazis annexed Stanisławów into the General Government, murdered the city’s Jews and terrorized the rest of the population. The Yalta treaty of 1945 brought the centuries-old Polish presence in Stanisławów to an end, incorporating it into the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine, and relocating the remaining Polish population to Opole in Silesia. In 1962 the city was renamed Ivano-Frankivsk.

Stanislaw was not a gifted tactician but a disciplined and tough soldier, who served the Polish Crown faithfully for over half a century. He was well liked by his troops for his fairness and concern with their welfare. They nicknamed him “Revera”, as he had a habit of interjecting his speech with “res vera”, Latin for “indeed”. The nom de guerre stuck so that he is better remembered by it than by his Christian name.

Stanisław Potocki donated his gilt mace or “buława”, symbol of his military power as commander-in-chief, to the monastery in Częstochowa in 1655, the year its successful resistance against the besieging Swedes rallied the country around their king. It remains there to this day. His grand-son, Grand Crown Hetman Józef Potocki, followed his example.

© 2023 Potocki Wódka. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

You must be of legal age in your country to view the contents of this website.