Alfred & Maria Potocki – Lwów – XIX

Alfred (1822 -1889) & Maria (1830 -1904) Potocki were what you would call today a “power couple”. They were both attractive, genuinely in love, heirs to great political traditions and large estates in Austrian Galicia and Russian Volhynia.

Alfred, born in Łańcut, received an excellent education and pursued a career in the Austrian administration. He served in the mid-1840s at the Austrian embassy in London where he developed a taste for British lifestyle and life-long ties with England.

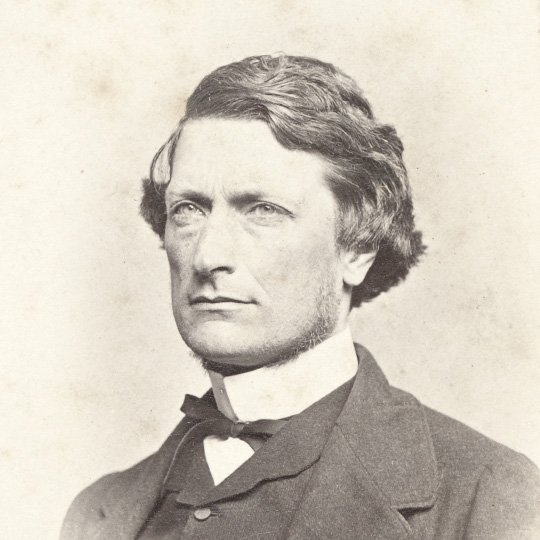

Alfred II Potocki, photography by Szajnok. © National Library Warsaw

His wife, the beautiful Maria Sanguszko, had a very unusual childhood. Her mother Natalia died a few months after her birth, while her father Roman joined the Polish insurrection of 1830-31, for which he was arrested and sent to Siberia in chains. In order to protect her and avoid confiscation of her vast family estates, young Maria was hidden with Ukrainian peasants for several years. Later raised by her grand-parents, she would grow up as a forceful and independent woman.

Following the 1867 compromise, Poles were given greater autonomy in the new kingdom of Austro-Hungary. Alfred, like his cousin Adam, entered politics by dint of his wealth and social position, but unlike the latter he enjoyed the trust of Emperor Franz Jozef. He was thus called to occupy prominent positions, first as Minister of Agriculture (1867-1870), briefly as Prime Minister at the time of Franco-Prussian war (1870-71), finally as governor of Galicia (1875-1883) in Lemberg (Lwów). Lacking a suitable residence, Alfred and Maria commissioned an elegant palace in French style on Copernic street.

The building remained in family hands until 1944 and is known today as the Potocki palace. It houses Lviv’s collection of Western art and is used by the President’s office to receive important guests.

Expand to Read More

Alfred, brought up between Łańcut and Kraków with his cousin Adam, pursued a more traditional career, naturally following the prerogatives afforded to him by his social standing and fortune.

His two sisters, Julia and Zofia, had married into leading Austrian families consolidating his prominent position in Vienna. After law studies, he was assigned as a young attaché in London in 1844, where his brother-in-law Maurice Dietrichstein was Austrian ambassador. The Embassy was located at Chandos House, which had become a focal point of social life under the previous Austrian envoy. The four years spent in England made Alfred into a lifelong anglophile and shaped his political views. Friedrich von Beust, who represented Saxony in London at the time, would later describe him as “an Austrian Whig”.

The timing of his return to Vienna coincided with the revolution of 1848. Unlike his cousin Adam who witnessed street battles in Kraków and Paris, Alfred saw the revolution unfold from the seat of power. The near collapse of the Habsburg empire caused by the secessionist insurrection of the Hungarians, which many Galician Poles had joined, was only averted with massive Russian military assistance. Alfred grasped the inherent fragility of the multinational Habsburg realm, to which he remained loyal, but understood the need for reform. He was appointed to the short-lived Parliament, exiled in Kremsier, as representative for the Łańcut district.

Alfred married Maria Sanguszko in March 1851. The only daughter of Volhynia’s Polish hero, Roman Sanguszko, Maria was beautiful and wealthy. Suitors were plenty but Maria fell for Alfred.

She was as domineering and impulsive as her husband was mild mannered and polished. Her dowry amounted to nearly 100,000 ha in Volhynia, which had once been part of the even greater estates of Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski. This considerable property, while strengthening Alfred’s financial independence and personal connections in Petersburg, would also constrain and direct his political orientations in regard to Russia.

Alfred II formally inherited Łańcut before marrying, but his energetic father Alfred I would not let go. The 1850s were politically dull following the centralist clamp down in Vienna, so the couple retired to their estates of Sławuta and Antoniny in the Ukraine.

Alfred learned a great deal from his father-in-law who had returned from exile in 1845, in particular in forest husbandry and above all in horse breeding. The Sanguszko studs were legendary. Roman’s father, Eustachy, started importing Arab stallions and mares directly from the desert in the early 19th c. The finest specimens were treated almost as family members, paraded around the dinner table, in truly oriental fashion. Roman modernised the breeding methods.

In 1851 he commissioned a racing track at Antoniny so that he could test the stamina and speed of his stock against recent imports. In time Alfred set-up a large-scale horse breeding operation of his own in Kurowice, a property east of Lwów, which supplied horses for the Łańcut estate. Potocki-Sanguszko thoroughbreds competed in both empires: Russian Warsaw and Kiev as well as Austrian Lwów and Vienna. This fine tradition would flourish under the next generation until 1914.

Alfred’s experience in Ukraine contributed greatly to the modernisation and industrialisation of his own estates. For example, he expanded Łańcut’s distillery production capacity and distribution network across the Austrian empire. The new rail line connecting Kraków with Lwów, administrative capital of Galicia, was completed in 1861. The train called at Łańcut and the stopping time was extended to allow travellers to acquire some of the Potocki liqueurs. A pioneering example of travel retail.

Alfred returned to politics after his father’s death in 1862, inheriting his seat at the Chamber of Lords in Vienna. A year later he was elected to the regional assembly in Lwów, a position he kept until retiring from public life, although he was often forced to switch districts among the many under Potocki ownership (Łańcut, Brzeżany, Podhajce) when running for re-election. The timing corresponded with the Polish uprising against Russian rule in January 1863. Like his cousin Adam, and even his father-in-law Roman, a veteran insurgent, Alfred viewed the armed rebellion as a pointless sacrifice.

The consequences of 1830 were still painfully obvious: inevitable Russian repression led to further weakening of the demographic, economic and cultural position of Poles in the Ukraine and Lithuania. Yet Alfred afforded material support to those fleeing arrest and refused to denounce the ephemeral Polish National Government.

The uprising was also doomed because the peasant masses failed to join. From the start, the insurgents promulgated the abolition of serfdom, but were unable to put it into practice. A year later, Tsar Alexander II abolished it in the former Polish provinces of the Russian empire, turning the tables on the insurgents who, for the most part, originated from the landed gentry. Memories of the failed 1846 insurrection in Austrian Galicia, and the massacre of landowners by peasant gangs, were fresh in the minds of all the protagonists.

As heir to the Holy Roman Empire, Austria could still contend for the right to lead a coalition of German states. Its humiliating defeat to Prussia in 1866 put an end to this ambition. From then on, the empire would have to balance between an increasingly restive mosaic of nationalities and the centralist policies of its German speaking elites.

The historic compromise of 1867, creating a dual Austro-Hungarian monarchy, while on the whole satisfying Magyar demands for autonomy, also encouraged Poles and Czechs to push for increased devolution and federalisation. However, Alfred Potocki was devoid of political ambition and loyal to the monarchy, as well as financially independent and well connected in Vienna and St-Petersburg, and he continued to enjoy Franz Jozef’s trust.

He was appointed Minister of Agriculture in Auersperg’s cabinet in December 1867, on the assumption that the Polish deputies would cooperate with the Government. The deal held, but Alfred proved unwilling to back Polish maximalist demands put forward by the Lwów assembly in 1868. He did not believe either in Polish initiatives aimed at mounting an alliance with France against Prussia and Russia, hoping to resurrect a Polish state. He refused for example to personally finance the short-lived “Correspondance du Nord-Est”, a news agency launched by the Czartoryskis of the Hôtel Lambert. Tensions between centralists and federalists eventually led to the fall of Auersperg’s government in January 1870 and the Polish faction soon withdrew its support.

Alfred Potocki was called back in April 1870 and appointed Prime Minister with a mission to break the parliamentary deadlock caused by a longstanding Czech boycott. The latter wanted Franz Jozef to recognise the crown of Bohemia, effectively paving the way for a tripartite state. Alfred tried and failed to unite Polish and Czech factions against German centralists. His social conservatism and belief that the Empire could not countenance conflicting national demands, quickly revealed him as a poor standard bearer for either group. Unable to form a parliamentary majority, he ended up leading a caretaker cabinet, assuming in addition the portfolios of Agriculture and Foreign Affairs.

With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war in July 1870, Alfred advocated Vienna’s neutrality, while the Galicians hoped to push Vienna to support the French. Alfred feared more military entanglements could have dangerous repercussions on the internal stability of the fragile multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian condominium.

Eventually the Emperor relented in exchange for an end to the Czech boycott. The compromise ended up satisfying only the German speaking faction of Bohemia, which duly sent its representatives to Vienna only to force Potocki’s exit in favour of a centralist candidate. His government lasted until February 1871. Alfred also disappointed his countrymen, including his cousin Adam Potocki. He nonetheless managed to authorise the use of Polish language in higher education and the appointment of a Polish Governor of Galicia.

Alfred was too useful a man to Franz Jozef to be allowed to retire. He briefly presided over the regional diet in Lwów, before being appointed Governor of Galicia in December 1875. He used his relative political independence to protect the local administration against encroachment from Vienna, while curtailing excessive manifestations of Polish nationalism, particularly those directed against Russia during the Balkan Wars of 1876-1878. The Emperor rewarded him by touring Galicia in 1880 and visiting Łańcut. Alfred encouraged Polish-Ukrainian dialogue and opposed Russian attempts to woo the Ukrainian population under the guise of panslavism and a shared Orthodox faith. He resigned his post in 1883 for health reasons and died in Paris in 1889.

Alfred held all the great decorations of the Austro-Hungarian empire including the Golden Fleece, as well as the Spanish Order of Charles III. The couple had four beautiful children: Roman (1851) future master of Łańcut, Julia (1853, Branicka), Klementyna (1856, Tyszkiewicz) and Józef (1862) who would inherit Antoniny.

At the end of his life Alfred Potocki commissioned Louis Dauvergne, a well-known Parisian architect, to design a modern residence on a plot he owned in Lwów. The project was completed in 1891 with the help of Julian Cybulski, a local architect. To this day the building maintains the neo-classical elegance reminiscent of 19th century France, which stands out against the distinctly central European atmosphere of the city.

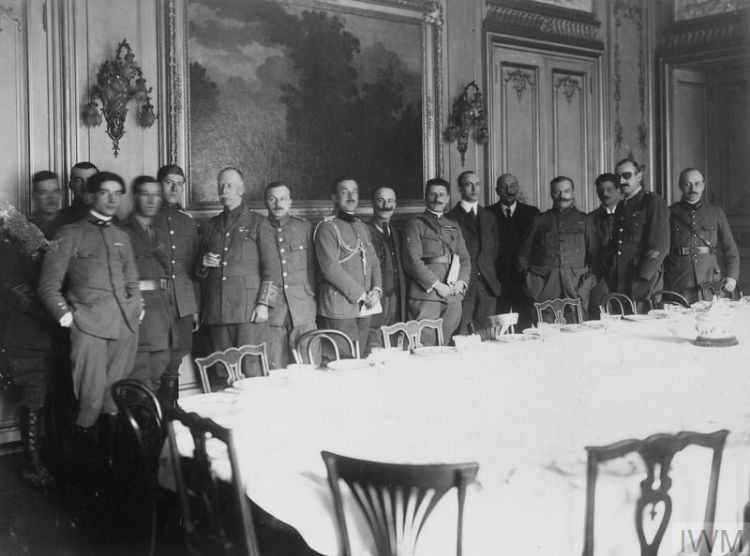

The Potocki palace had an interesting history during the post-WWI years. As the Austrian retreated from the eastern front in November 1918, they handed control of Lemberg (Lwów or Lviv) to the Ukrainians which elicited the immediate armed reaction of the Polish population, mostly young boys, women and older men, who considered the city theirs. The conflict quickly escalated into a guerrilla war in the winter of 1918-1919 which was only resolved to the advantage of the Poles the following spring. During that short period the Potocki Palace served as the headquarters of the American Relief Administration, which had been set-up by Herbert Hoover to provide humanitarian help to civilian populations in newly independent Poland.

Its first representative in Lwów was a young American named Merian C. Cooper. The palace also served as a venue for several French-led missions striving, fruitlessly, to negotiate a truce between the Poles and the Ukrainians in early 1919.

Back in Paris in the summer of 1919, Cooper and Cedric Fauntleroy, recruited demobilised American pilots to fight as volunteers in the Polish army against the Bolsheviks. They would be remembered as the Kościuszko Squadron.

By a strange twist of fate, one of them, Edmund P. Graves, a Harvard graduate, crashed his plane into the palace’s roof during a flight demonstration on November 11, 1919. He would eventually be buried at the Łyczaków cemetery and honoured by a memorial to fallen American pilots during the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1919-1920.

© 2023 Potocki Wódka. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

You must be of legal age in your country to view the contents of this website.