Natalia Potocka – Natolin – XIX

Natalia Potocka (1807 -1830) is a romantic albeit tragic figure. The only daughter of Alexander and Anna Potocki née Tyszkiewicz, she is forever associated with the estate, Natolin, bearing her name.

With the birth of their children, the young couple moved out of Wilanów to settle in a neo-classical house, set in a park on a hill surrounded by forest. With the help of her father-in-law, Stanisław Kostka Potocki, Anna set about redecorating their new home and landscaping the park. So involved was she in the endeavour that she renamed the house Natolin after her daughter’s birth.

The beautiful Natalia married Roman Sanguszko in 1829, but alas died shortly after giving birth to Maria. Her widowed husband, stricken with grief, joined the Polish insurrection of 1830 against the Russians and was sentenced to hard labour in Siberia. Natalia’s father erected a mausoleum in her memory in Natolin’s park.

But love conquers all and her memory lives on. Today Natolin, located on the southern outskirts of Warsaw, is a well-preserved memento to Natalia Sanguszko’s short life. Since 1992, Natolin it is the elegant and secluded seat of the College of Europe. The palace has undergone extensive restoration and modern facilities were added. Yet, the aura of the place remains untouched, mostly thanks to the old-growth woods surrounding it.

Expand to Read More

The original building served as king Jan III Sobieski’s hunting lodge in the vicinity of his Wilanów palace. Set on a small scarp, it was surrounded by a dense forest and bogs fed by the adjacent Vistula river. King August II Wettin leased the grounds from the next owners in the 1730s, turning it into a pheasant shoot, hence the name of “Bażantarnia” or “Pheasant lodge”. What had been valued as a natural barrier protecting the southern approaches of Warsaw and as rich hunting grounds, grew in recreational appeal towards the end of the 18th century.

August Czartoryski, Wilanów’s next owner, amassed an enormous fortune through marriage and business acumen. He nurtured ambitions to claim the throne of Poland for his son. Even if royal power eventually eluded the Czartoryski “Familia”, his two children competed on a par with the last king of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski, for political influence and artistic pre-eminence. Adam, settling in Puławy, continued his father’s ambitious political agenda; Izabela, married to Stanisław Lubomirski, further developed and embellished her vast real estate portfolio, in particular Łańcut and Wilanów.

Izabela instructed a young Saxon architect active in Warsaw, Szymon Bogumił Zug, who had been working for her father, to modernise the palace in Wilanów and to build a summer house in place of the old pheasant lodge. Zug applied a neo-classical design, inspired by the works of the Englishman William Chambers. The side facing the escarpment boasted a semi-circular open patio, topped by a cupola supported by six Ionian columns, opening onto the long view below.

Izabela also transformed the untamed forest into a park. Wide perspectives, radiating fan-like from the house, were cleared. Excess water was drained and plans were made to add further neo-classical structures. She also hired Vincenzo Brenna, whom her son-in-law had recruited in Italy, to decorate the pavilion’s main rooms in the style reminiscent of ancient Roman villas. His work in Warsaw was noticed by Paul and Maria Romanov, then travelling incognito in Poland. The future Tsar Paul I went on to hire Brenna to decorate his personal residence in Gachina and, upon accessing the throne in 1796, extended his commission to the imperial residences of Pavlovsk, Peterhof and Tsarskoye Selo.

The last two partitions of Poland of 1792 and 1795 brought war and destruction and suspended plans for further improvements. Warsaw had come under Prussian control and Izabela, preferring to live under Austrian rule, transferred her property in 1799 to her daughter Alexandra and Stanisław Kostka Potocki.

Their son, Alexander Potocki, married Anna Tyszkiewicz who bore him August in 1806 and Natalia in 1807. The young couple was longing to move out of Wilanów and chose to settle in the garden villa which was also renamed Natolin in honour of their baby girl.

The making of Natolin corresponded with a new and important chapter in Polish history. Napoleon, having defeated the Prussians at Jena in 1806 and the Russians at Friedland in 1807, established the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. Granted autonomy, the Poles modernised their institutions and renewed ties with France, hoping to eventually restore their statehood.

Stanisław Kostka and Anna, a keen student at her father-in-law’s side, worked in tandem to redesign, extend and furnish the interiors of Natolin. Stanisław instructed Piotr Aigner, his close collaborator and architect, to replace Brenna’s paintings with white stucco ornaments inspired by the new Empire style gaining in popularity across Europe. They were realised by Wirgiliusz Baumann who had decorated the royal castle earlier in his career. Anna furnished the interiors at great personal expense, as her diary testifies, at times selling some of her jewellery to pay contractors.

Her elegant prose deserves being quoted en français dans le texte : “Je dessinais tous les plans, m’intéressais à tous les détails. Sans les connaitre, je rêvais l’Italie, la Grèce… Mon amour-propre ainsi que mes prétentions se trouvaient concentrés à Natoline, dans ce petit-chef d’œuvre qui me paraissait digne d’immortalité. Lorsque nous manquions d’argent, je vendais des diamants afin d’acheter du marbre et du bronze…Heureux temps où mes visions n’eurent jamais d’autre cause que le trop plein de mon imagination ! […] Avec quelle impatience j’attendais le jour pour jeter sur le papier les idées que le calme de la nuit avait fait germer.”

Anna’s greatest influence however was on redesigning the park. The couple sought to create a landscape similar to an English parkland, by harmonising the natural growth of the forest with eye-pleasing design. Only three access roads were maintained. Priority was given to planting trees while preserving the original diversity of the old-growth forest. Stanislaw entrusted Karl Bartel, an excellent gardener brought from Erfurt by Izabela Lubomirska, with coordinating the project. Natolin reached its apex in the second decade of the 19th century and was considered one of the finest parks in Poland.

Happy times did not last. Alexander and Anna divorced in 1820 and Stanisław Kostka died the following year. As part of the divorce settlement Anna took all the furnishings with her, while Alexander moved back to Wilanów and remarried.

Their beautiful daughter Natalia had many suitors, including the son of Lord Holland, whom she had met in Naples. She eventually married the handsome Roman Sanguszko in 1829 but died tragically the following year shortly after giving birth to Maria. Her premature death and Roman’s subsequent ordeal in Russia (see side story) sealed her association with Natolin for posterity.

To honour his daughter’s memory, Alexander erected a mausoleum stylised after ancient Roman sarcophagi. The resting figure of Natalia, is the work of Italian born Ludwig Kauffman, who had studied under Canova and was clearly inspired by his teacher’s marble statue of the Nymph Dirce, now in the British Royal Collection. Kauffman is also remembered for the mythological figures adorning today Warsaw’s Łazienki park.

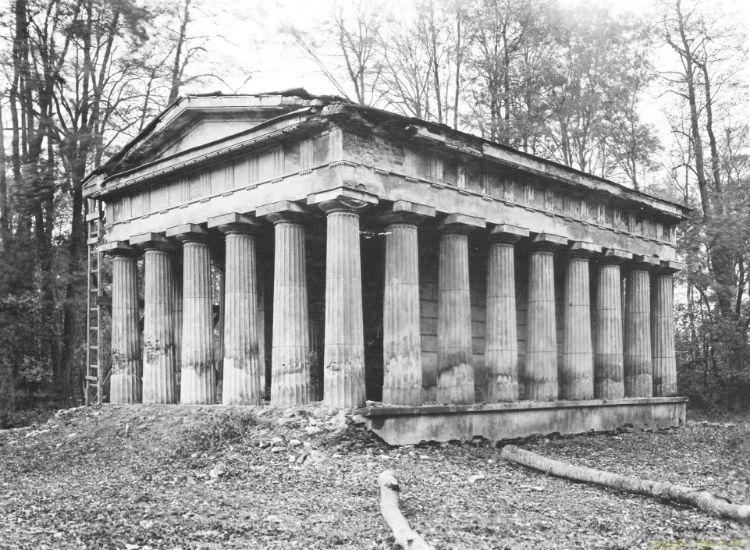

Henryk Marconi, a prolific Italian architect active in Poland, designed the bridge leading to the monument, guarded by four sleeping stone lions. Alexander Potocki commissioned him to build a neo-gothic “Mauresque” gate on the eastern side of the estate. He also erected a pocket Doric temple in the park, originally designed by his father and Aigner, and modelled after the impressive Greek temple of Poseidon in Paestum.

Wilanów passed onto the Branicki family in 1892, who alas neglected Natolin. In 1922, brothers Józef and Roman Potocki, seized the opportunity to lease it for 20 years from their cousins as a summer retreat for their recently widowed mother Helena. Conveniently located close to Warsaw, surrounded by a magnificent forest, it was an ideal summer residence. Upon arriving in Poland in 1937, US Ambassador Anthony Biddle and his wife Margaret occupied it for a few weeks while their Warsaw home was being refurbished, and even hosted a Fourth of July party.

Following the Warsaw uprising in the summer of 1944, Natolin was badly damaged by its German occupiers, who used Natalia’s monument for target practice. The estate was confiscated the following year by the Communist regime and long served as a discrete hideaway for the red nomenklatura. In 1992 Natolin was leased to the College of Europe, which was looking to open a sister institution in Eastern Europe. The Natolin European Centre has since thoroughly restored the site.

The surrounding forest, encompassing just over 100 ha, was turned into a nature reserve in 2000. It is now a precious haven of undisturbed flora and fauna on the city’s edge, and in some places contains remnants of the vast Masovian primeval forests, flourishing as late as the Middle Ages. The most valuable stands include historic oaks, some of which are over 300 years old.

To all of those who built, preserved and restored Natolin. May their work inspire their successors.

Roman Sanguszko (1800-1881), Natalia’s young husband, bereft with grief at her death, crossed the border into the Duchy of Warsaw to join the Polish insurrection, which broke out in November 1830. In order to protect his family and fortune, he did so under a borrowed name: Stanisław Lubartowicz. Taken prisoner by the Russians a few months later, he was recognised and put on trial in Kiev. His rebellion under a false identity was considered an act of high treason punishable by death. Young Sanguszko had indeed served, at the behest of Tsar Alexander I, in the imperial guards as well as in the Russian embassies in Naples and London.

Offered to renege on his involvement on account of his wife’s premature death, Roman persisted and declared he had acted “from conviction”, which would later become the Sanguszko family motto.

Thick bribes spared his life but not his freedom. Roman was sentenced to exile in Siberia and by personal order of the Tsar Nicolas I, was to reach his place of detention on foot and in chains (“пешком и в цепи”), a harsh treatment usually meted out to common criminals. Roman’s mother appealed to Empress Alexandra, whom she had befriended in earlier years in Berlin, alas to no avail.

Although his case had not elicited the sovereign’s clemency, his posture of stern patriotism earned Roman unwanted fame and admiration throughout Polish lands and even as far as England. More painfully for him, along his long journey from Orel to Tobolsk, via Kazan and the Ural mountains, curious villagers would often line the roads to gape at “Sanguszko”, former owner of 25,000 souls now passing through in rags and chains.

As a way out of Siberia, Roman volunteered in 1834 to join the Tenginski infantry regiment as a private. Based in the Kuban, he fought for four years the mountain tribes of the Caucasus. Twice wounded, he was restored in his civil rights and promoted to second-lieutenant, yet the Tsar would not let him go. Finally transferred to Moscow, it was not until he had lost his hearing on account of an infection, that Roman was freed in 1844. Before returning to his estate in Sławuta, Roman made a thanksgiving pilgrimage to the Holy Land, which he also used as an opportunity to acquire several Arabian horses for the famous Sanguszko stud.

The trials Roman endured with humility and dignity strengthened his faith and instilled him with a thirst for positive, creative work. Cut-off from the comfort of European civilisation for many years, Roman made remarkable observations, worth quoting from a letter to his father in 1838: “What enormous enterprises are being realised in the United States without any force other than the concentration of means. It is a country pulsing with work. Our great misfortune is that we do not work together, everyone loses energy acting alone. In America, a single individual will meet ruin several times in a lifetime, but will also earn many fortunes. We waste ourselves because we do not work creatively. If I say „We”, it is because I identify with the land that bore me and the people who occupy it”.

Roman’s estate, extending over 100,000 hectares, had escaped confiscation by being transferred to his daughter Maria. Striving to make up for lost time, he harnessed the great means at his disposal to industrialise and modernise his holdings, in particular by building the first sugar refineries in Ukraine. He also abolished serfdom on his property in 1848, following the example of his Galician brethren but fifteen years ahead of abolition throughout the Russian empire. Roman Sanguszko cut an imposing figure in his old age. Devoted to his family and the land of his ancestors, living a spartan life, communicating with a pencil and notepad, he was revered by Poles and respected by Ukrainians. He truly had earned the sobriquet “The Unbroken Prince”.

Roman’s exemplary life was a scenario better than fiction. His great-grandsons, Roman and Józef II Potocki, used the archives saved from Antoniny to commission a monograph published in Warsaw in 1927. Yet the most enduring tribute is owed to Józef Korzeniowski, aka Joseph Conrad. Born in Volhynia, brought up in the cult of the Polish insurrectionists, he wrote a short story titled “Prince Roman”, which was published posthumously in 1911 in “Tales of Hearsay”. The first paragraph is worth quoting: “Events which happened seventy years ago are perhaps rather too far off to be dragged aptly into a mere conversation. Of course, the year 1831 is for us a historical date, one of these fatal years when in the presence of the world’s passive indignation and eloquent sympathies we had once more to murmur ‘Vo Victis’ and count the cost in sorrow. Not that we were ever very good at calculating, either, in prosperity or in adversity. That’s a lesson we could never learn, to the great exasperation of our enemies who have bestowed upon us the epithet of Incorrigible….”

© 2023 Potocki Wódka. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

You must be of legal age in your country to view the contents of this website.